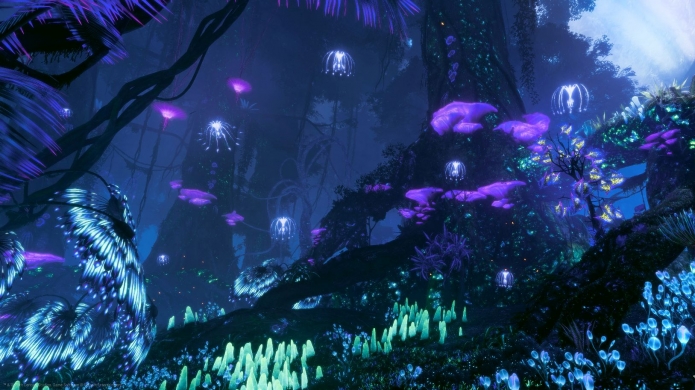

Why You Should Look at Avatar: Frontiers of Pandora with Eyes Wide Open

Post by Steve Farrelly @ 01:10pm 27/06/23 | Comments

We take a deep look at Avatar: Frontiers of Pandora and discuss why you shouldn't be dismissive of what it's attempting to do...

There is no question the Avatar films are divisive among casual and hardcore moviegoers alike. Some think James Cameron’s politics are either too on the nose, too liberal (not the Aussie political party) or plain too simplistic. While others find the colour palette of the whole thing a bit young on the eyes, and maybe not entirely for all audiences. But then there are those who think the films are works of art; epic moments in cinematic history that remind us how actions ought to be shot, or that the politics embedded within are, actually, quite complex, layered and poignant in relation to both our own history and in the context of our modern society.

And everyone is, of course, right -- because opinion is just that, and you know the saying about everyone who has one…

So Avatar: Frontiers of Pandora has already been met with scepticism and derision. But you’d be putting all of your unobtanium in the wrong refinery if you were so flippant about this. Frontiers is very much a standalone effort, separate from the films (in the sense it's not a basic licensed recreation of 1 and 2), and it comes from the technical and open-world geniuses at Massive Entertainment. And, really, all of that should be enough to pique your interest. This leaves us with a robust, unexplored-in-film, landscape to build upon with Ubi Massive having been given a huge amount of creative freedom from Jim and Lightstorm (Jim told us, directly). All of which is easily summed up, from the outset, by the fact Frontiers is actually a first-person action-adventure game set in a vast open-world, rather than something done in the third-person.

Author Christian D. Read on Avatar and its Complex Nuance

One of the things that always takes me aback about the Avatar films is just how sustained in attack and in vitriolic attack they are in their criticism of not just American Imperialism but how frank they are on attacking the unhuman nature of capitalism.

Jake Sully, the hero, is crippled in a war. We can’t know what it is, but it has left him in a wheelchair. And although this is the future, and the technology exists to recreate entirely functional bodies, Jake is just a grunt, used up in an imperial war. It isn’t until he shows further use to the State and the Corporations that he is given his new form.

There, he comes to realise the elven Na’vi, the inhabitants of the paradisiacal world of Pandora, live harmoniously with their planet and reject human technology. Simply put, because they do not need or want it. Not that this matters to the megacorps who want the unobtanium, (an old SF joke straights never got), Pandora’s second most vital asset.

Jake joins the Na’vi, but only after he proves his worth, which takes some doing. “Baby,” they call him. He’s far from white saviour, a reading only the witless could have...

In case you’re not up to muster, the game is set some 15 years after the incidents of the first film. The humans in this storyline have continued their oppressive and subjugative ways, kidnapping a handful of children from different Na’vi tribes and raising them, almost, as child soldiers; indoctrinated against Pandora and its denizens as part of the cleverly titled ‘Ambassador’ program. When Sully and co wreak havoc in the timeline of the first film in 2138, you’re put into cryosleep in an effort to save you from the chaos that ensues, only to awaken some 15-years-later in 2154 in the abandoned stronghold you called home most of your young life.

From here, the game lets you create your own Na’vi with an in-depth character creation tool and once you’re set, you’re tasked with reconnecting with Pandora and your stolen history across a vast expanse set on the planet’s Western frontier. And while that might sound easy enough, what you find is that there’s a huge amount of mistrust leveraged against you among the many tribes you come across -- an animosity designed to feed and contextualise gameplay where performing quests and more for these disparate groups will help you win favour, grow your reputation and, more importantly, strengthen your connection with the land, which in gameplay terms means getting stronger, gaining new abilities and tools and opening up the game even more. It's a tried and tested loop, but in Frontiers it feels natural and right from a philosophical sense, which is a bit rare in games based on licenses (that aren't Star Wars).

The world Massive has crafted here, even from our limited exposure to it, is massive (could have used other adjectives, but nah… ). And one of the key things you’ll do in it is gain mounts, the best of which will be your own Ikran -- the dragon-like creatures made famous from the first movie and once you’ve bonded with it, you can literally fly anywhere in the game’s playspace. And considering there are numerous floating locations, it means said playspace isn’t just the land upon which you walk (or ride -- there are other mounts to bond with), it’s also above and below (there will be water biomes and floating island biomes and various others, all distinct from one another, and each featuring unique resources and emergent gameplay opportunities.

"You’ll be able to enhance these resources through various means and by harvesting them "correctly", though it’s not always guaranteed you’ll be successful...”

So throughout you’ll meet other Na’vi, and as with the varied game-world mentioned above, each tribe is different with different needs, customs and resources. Throughout your journey you’ll meet various vendors and gather all manner of ingredients through harvesting for crafting purposes. You’ll be able to enhance these resources through various means and by harvesting them "correctly", though it’s not always guaranteed you’ll be successful, and all of this is designed to enhance you as a Na’vi coming (back) of age. You can even customise and upgrade your Ikran as this companion will be with you for life, further enhancing your renewed attachment to the land.

Continued from Above…

Sully betrays his race not only because of the beautiful floating forests of Pandora, or to get some blue girl action, but also because of his disgust that his fellow humans largely know what they are doing is a cosmic sin, they just know a paycheque awaits the doing of it.

Stephen Lang’s monstrously cruel marine captain isn’t scary because he’s a rough customer, rather, he puts his personal best interests over the preservation of heaven. In the second film, a marine biologist notes with little enthusiasm that the sentient, peaceful and compassionate whales are being hunted for the immortality juice within their brains. He looks on as whale kids are targeted, knowing mother’s won’t abandon their young. “This is why I drink,” he says, despairingly. But he’s still there when his next shift comes around. Even Sigourney Weaver’s brilliant scientist, aware of the incredible interconnectedness of the planet, still works to defile it for cash. Cameron just isn’t critiquing the profit-seeking totalising goal of capitalism, he’s criticising individual actors within it. In the Avatar movies, the true revolutionary offers their life to the cause.

While a few of the Pandoran workers do join Jake, it does not take away from the magnificent spectacle of the destruction of the earthican bases, perhaps the finest cinematic display of asymmetrical warfare in film history.

It is impossible to see this without thinking of other times Empires have ground themselves to powder against far less technological, but far more committed peoples, from pith helmets and martini rifles in the Sudan and Afghanistan, to the jungles of Vietnam...

The story of Avatar is one of race betrayal. Sully, as author Christian Read points out in our box out, is no more a so-called ‘white saviour’ trope than he is a functioning human. “He betrays his race not only because of the beautiful floating forests of Pandora, or to get some blue girl action,” Read indulges. “But also because of his disgust that his fellow humans largely know what they are doing is a cosmic sin, they just know a paycheque awaits the doing of it.” (Be sure to read the full box out for a different view of the politics of Avatar.)

So that reclamation of the land is part of your journey as a Na’vi to cleanse the infection of humans and human technology and its rape and pillage of the land and its precious resources. It’s how you gain favour with your Na’vi brothers and sisters and how you help heal your own internal wounds; your own traumas. And more importantly, it’s how you become whole again.

Of course, there’s going to be nothing better than using superhuman abilities against the RDA, and as you’ve seen from the game’s gameplay trailer taking down giant human vehicles of war with Na’vi weapons created from the land you now protect; forged of harvested goods because you learnt the right way to do it from your Na'vi brethren-turned-teachers is just going to be fun. So much fun. And if you’re still in the camp of “yeah but lol FernGully”, at least acknowledge that in FernGully Zak never had a shotgun or flash grenades.

Excitingly, the game will feature a story, of course, but Massive has said you're not locked into a singular path and this Western frontier of Pandora is full of things to discover and explore. The richness of the game-world couples with those of the movies, but as mentioned in our openining salvo, the studio has also been given a lot of freedom from Cameron and Lightstorm. And fans of JC will know he doesn't just align himself with anyone and is something of a tech geek himself, so it's reassuring knowing he and his cohorts have not just full faith in Massive, but also a guiding hand in it all.

"This fresh standalone chapter in the Avatar universe could be the beginning of an expanded ruleset that finds its way not only into the movies yet to come, but in all forms of other Avatar media in the pipeline...”

You’ll be able to play through the entire Avatar: Frontiers of Pandora campaign in two-player co-op as well, with each player able to take to the skies on their Ikran or to ride across the plains on any one of the game’s ground-based mounts, which should have plenty of you excited. This fresh standalone chapter in the Avatar universe could be the beginning of an expanded ruleset that finds its way not only into the movies yet to come, but in all forms of other Avatar media in the pipeline, and honestly, we can’t wait to play it when it drops later this year on PC and next-gen consoles, December 7.

In Conclusion…

Avatar also indulges -- and this is rare for a 21st Century film -- in critiques of spirituality. Pandora has a kind of planet wide biological internet. This is a materialist, dialectic conception of the afterlife. Believing in God is religion, believing in Pandora is not an act of faith.

When Stephen Lang’s character, and his undead bro goons, return in the second film, we understand he is a kind of clone, with his predecessors knowledge and grudges. But beneath this simple bit of SFnal logic, is a greater critique still. For the capitalist classes, heaven is dying in the wars of the fascist agenda, only to be born again in a new war, endlessly born to die again, so the wealthy can be wealthy endless. Even heaven is hell, to James Cameron, if your God is money.

Make no mistake, the Avatar film series are not simply against the bad corporations or a mewling, liberal cry for empathy. They are a call to revolutionary violence.

-- Christian D. Read

Read more about Avatar: Frontiers of Pandora on the game page - we've got the latest news, screenshots, videos, and more!

Latest Comments